A la une du blog

Protection de la vie privée et des données personnelles : vers la fin du libre accès du public aux informations inscrites au registre des bénéficiaires effectifs

Le 22 novembre 2022, la Cour de Justice de l’Union Européenne a jugé que le libre accès du public aux informations portées au registre des bénéficiaires effectifs des sociétés est illicite.

Tribune de Me Philippe Touitou dans les PETITES AFFICHES DES ALPES-MARITIMES Concurrence déloyale : création par un salarié en exercice d’une société concurrente de son employeur

Le 7 décembre 2022 la cour de cassation a jugé que constituent des actes de concurrence déloyale la création par un salarié en exercice d’une société concurrente de celle son employeur, ainsi que la détention, [...]

Toute notre équipe vous souhaite de belles fêtes de fin d’année et vous présente ses meilleurs vœux pour l’année 2023 !

Nous avons encore passé une année aussi intense que remarquable, en termes de réalisations, aux côtés de nos clients et partenaires. Alors, comme chaque année, nous remercions chaleureusement nos clients, pour leur fidélité et leur [...]

La société Apple privée de la marque “Think Different”.

Par arrêt du 08/06/2022, le Tribunal de l'UE a débouté la société Apple de ses recours contre plusieurs décisions de l'Office Européen pour la Propriété Intellectuelle (EUIPO). A la demande la société Swatch, l'Office avait [...]

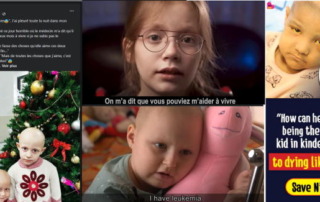

Philippe Touitou interviewé par le quotidien LE MONDE : Derrière les publicités montrant des enfants atteints d’un cancer, les dérives du tourisme médical en Israël

Une campagne publicitaire israélienne, montrant des enfants gravement atteints de cancers, a été diffusée en France et dans d’autres pays à la fin de 2021. Par Damien Leloup, LE MONDE, 24 janvier 2022. Lien permanent [...]